As I Found It:

My Mother’s House

Russell Hart

Russell’s solo exhibition presents an alternate look at resistance, a resistance to change, a resistance to letting go, and a look at what gets left behind… This look at one person’s process to honor, reflect and move forward is presented in tandem with Resistance: Seen or Unseen, a juried call for entries exploring resistance in all its varied forms.

Presented in our Focus gallery is a selection of photographs from Russell’s recently published book, As I Found It: My Mother’s House. Copies of the book are available and we are hosting a talk and book signing on Friday, July 18th from 4:00 – 6:00 pm, and we hope you can join us for this unique presentation.

– David DeMelim,

Managing Director,

RI Center for Photographic Arts

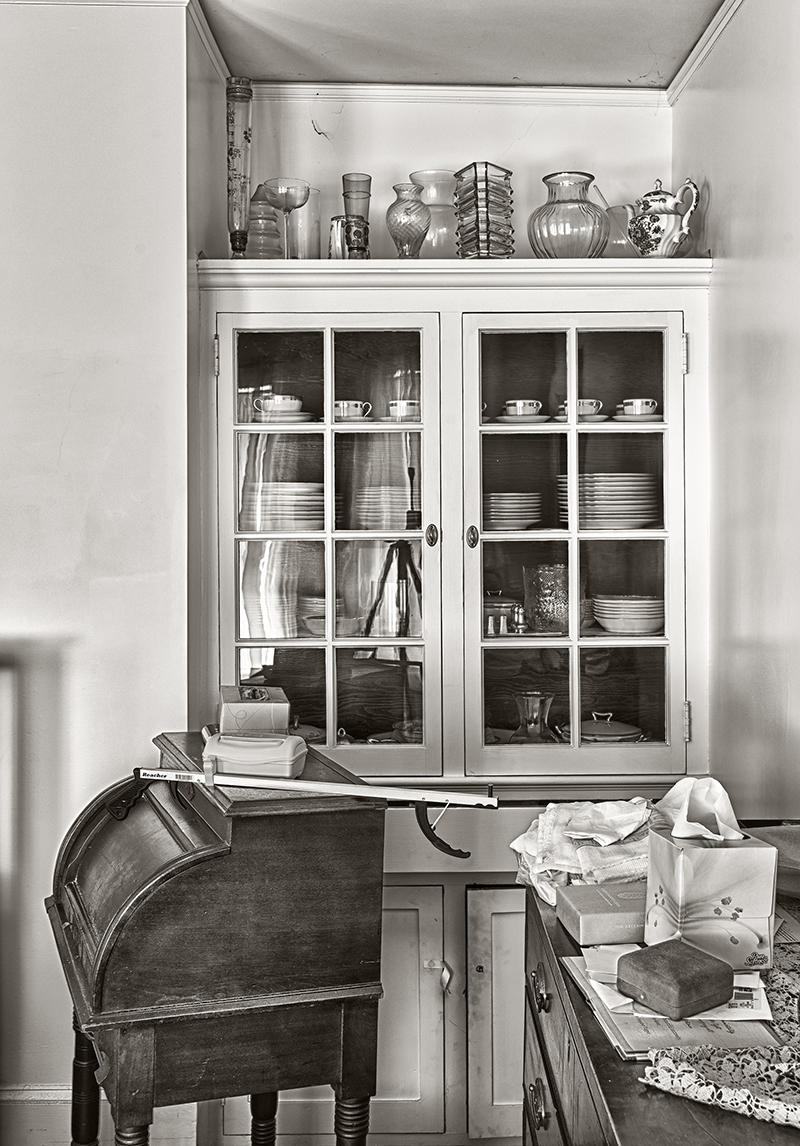

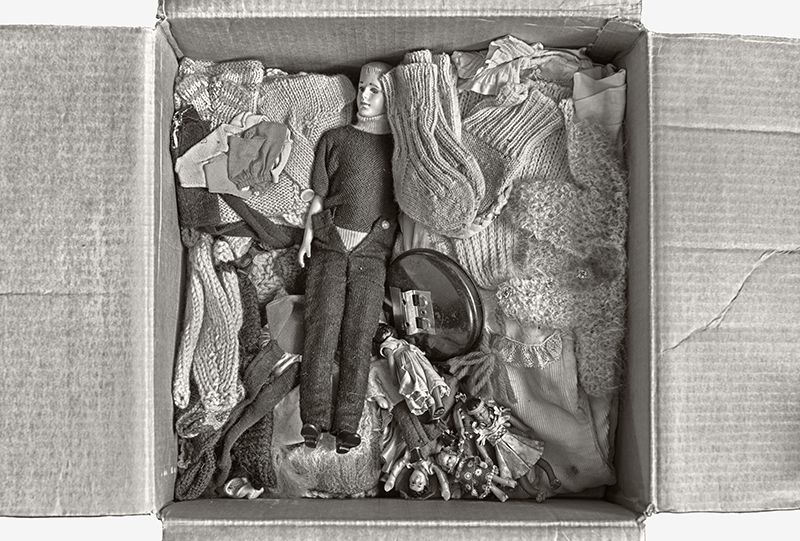

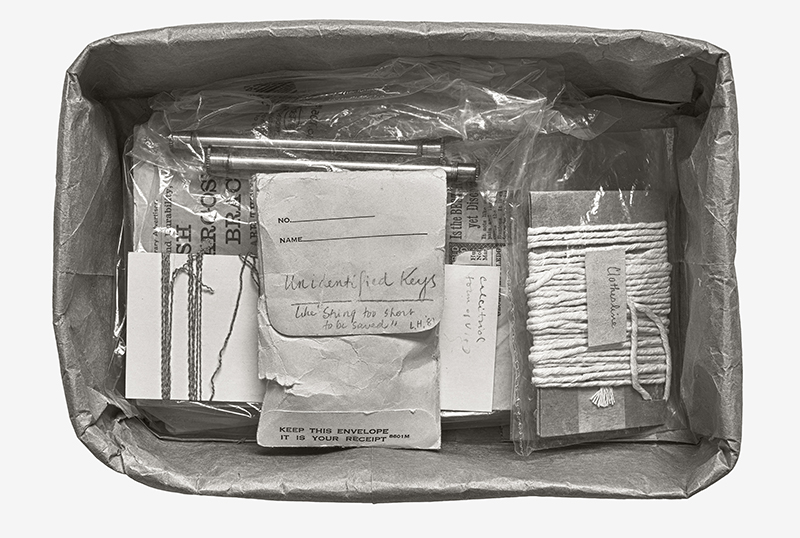

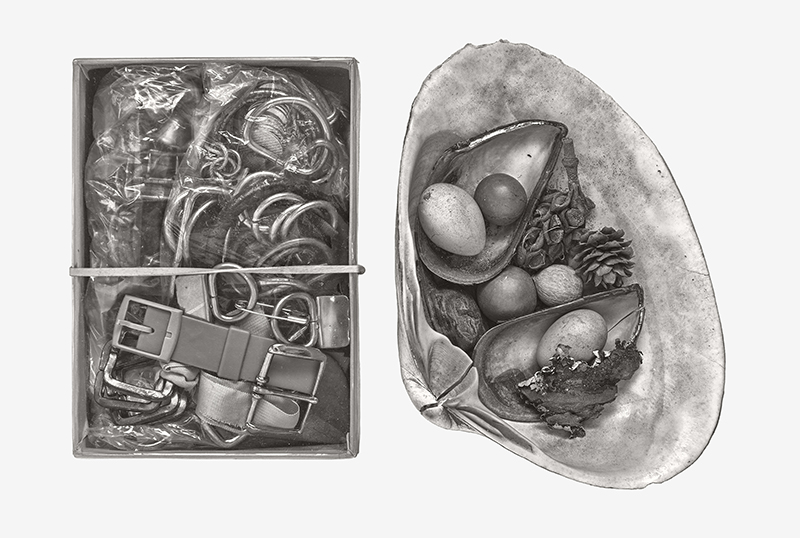

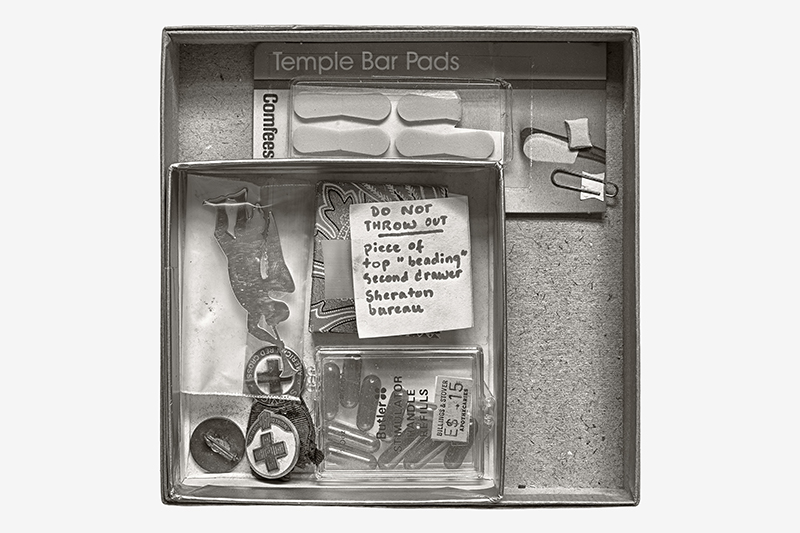

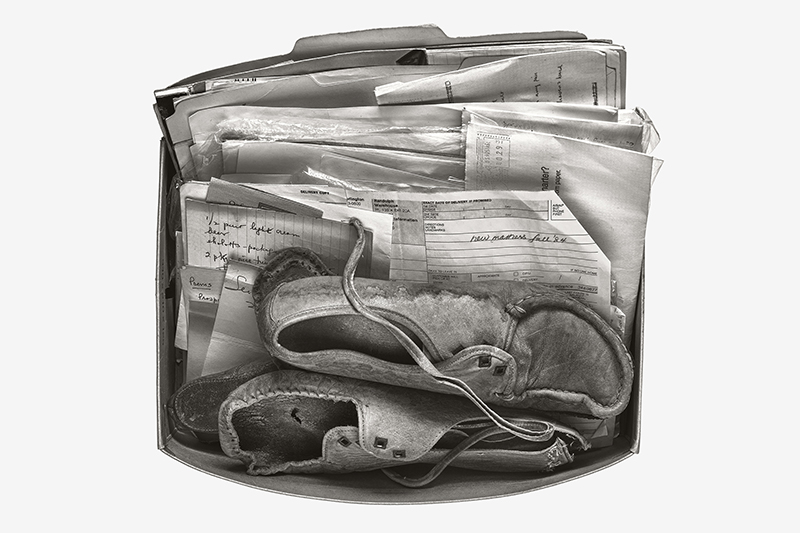

My first instinct was to photograph the interiors that were so familiar to me as I emptied them of their life. In the vastness of what my mother had squirreled away, though, were hundreds of “trays”—usually cardboard boxes she had cut the tops off with a utility knife to a carefully measured height—in which she’d organized groups of related items. Most of these items had outlived their usefulness, let alone their meaning. I also began to photograph these arrangements, by the light of an attic window, using a meticulous technique that preserved all their detail and tonality. Toward the end of my clearing out the house these subjects, essentially still lifes, took over the project.

While the images in this book are documentary, they’re more personal—more about my own life and family—than any I’ve ever made. My photographs have always looked outwards, so I’m not altogether comfortable in sharing this body of work. Yet my hope is that it connects to the experience of anyone who has dealt with the decline of parents, and to the way in which that struggle revisits and reinvents the meaning of family. I think it also addresses, by inference, dementia’s destruction of identity and history. All that said, I don’t want people to come to the work with too much information or too many preconceptions. I want viewers to be able to “read” the images’ content not only for what might be gleaned about my mother’s life and personality, but also for evocations of their own experience.

As I Found It: My Mother’s House, Russell Hart

Russell Hart’s solo exhibition is presented in tandem with Resistance: Seen or Unseen Juried exhibition

Opening Reception: July 17th, 5:00 – 8:00 p.m.

Book Signing & Artist Talk: July 18th, 4:00 – 6:00pm

Gallery Night Providence Reception: August 15th 5:00 – 8:00pm

On View: Thursday, April 17th – September 12th

Artist Statement As I Found It: My Mother’s House

Sometimes I envy my baby-boomer friends for having lost their parents quickly. Mine left this life piecemeal. It took my father two painful years to die from cancer, and soon after, without her husband to moor her, my mother began her long descent into profound dementia. More than ten years later, when she could no longer live alone, it fell to me to empty the rambling, creaky New England Victorian she had inhabited for over four decades. Paperwork piled high on her desk and most other available surfaces told a sad tale. Starting with her latest bills, greeting cards, and copious notes to self I peeled away the layers, and at the very bottom found myself back at 2001. My mother’s life, in an emotional sense and as a realm she could successfully manage, had ended the year my father died.

My undertaking took the better part of two years. I spent nearly half that time living in the house alone, plowing from morning to night through rooms gorged doubly by outright hoarding and the Yankee custom of handing down meaningful objects. Much of what I unearthed was unfamiliar to me because it had been packed away for generations, sometimes a century. It ranged from unusably practical to historical—from saved bits of string to the hand-woven wallet an ancestor had carried into the French and Indian War.

My determination to find a home for things that had some life left in them prolonged the job. I delivered three carloads of fabric from clothing my mother had dismantled—she removed every last stitch, laundered it all, and neatly folded it or clipped it to coat hangers—to the local quilting guild. She had planned to take up the craft, one of the few she’d never explored, but my father’s death crushed her enthusiasm.

Beyond things in plain sight the house contained more than a thousand cardboard boxes, mostly stacked high against attic and basement walls. Clusters of smaller boxes were often nested inside the large ones, each containing an assortment of items: my grandmother’s sewing notions, which themselves often predated her; waistbands detached from my father’s “skivvies,” as he called them, to hold things together; buttons cut from clothing too frayed to wear, saved for unimagined projects. Some of it was purely sentimental, such as the collars and tightly coiled leash with which we walked the dog I grew up with, loved most by my mother, already forty years gone.

Much of the boxes’ content appeared to be neatly ordered, but in ways that would have made sense only to my mother, a scheme she was no longer able to explain. Boxes and their artifacts were often heavily annotated, on index cards or Post-It notes as old as their invention—as if my mother had captioned an entire life in the tiny, perfect handwriting that now abandoned her. She was obsessive-compulsive, a behavior that Alzheimer’s cured.

My task was the most solitary, emotionally difficult thing I’ve ever done, made doubly hard by daily visits to my mother’s “memory care” facility, where her personality and strength were ebbing away. Thinking it might mitigate my grief and loneliness I started taking pictures as I worked, though not for memory’s sake. I don’t think my parents had a clue about the magnitude of the job they’d left me, nor was there any way I could explain to my mother, in her impaired state, what I was doing or ask her permission to do it. Had she understood that I was poring over her life history piece by piece, and deconstructing the years of work she’d invested in preserving it, she would have been distressed. I think she would have been even more unhappy had she known I was making the photographs in this book because she was always a private person, to use that familiar tautology. I needed to do it, though, to extract something positive from the experience.

– Russell Hart

About Russell:

Russell Hart’s work has been widely exhibited at galleries and museums that include the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Newport Art Museum, Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the New Britain Museum of American Art, and the DeCordova Museum in Lincoln, Massachusetts, among many others. His prints are held in the collections of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University, the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, NY, and various other public and private collections. He has been the recipient of numerous residencies and fellowships in photography, including three traveling fellowships awarded by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. His artwork has been featured in a variety of publications, including Harper’s Magazine, Camera Arts, Fotografare, and The Boston Globe Magazine.

Hart has taught photography at Tufts University and the Boston Museum School, and currently teaches in the master’s in digital photography program at New York’s School of Visual Arts. He was formerly Executive Editor of American Photo magazine, where he wrote about photography for many years. His writing on photographic subjects has also appeared in The New York Times, Men’s Journal, and La Repubblica delle Donne, among numerous other publications.

Hart was a member of the American Photo editorial team that won the American Society of Magazine Editors’ 1994 National Magazine Award for General Excellence. He received the 2003 Gold Medal for Best General Feature from the International Regional Magazine Association, and in 2006 the Lucie Foundation’s award for best photographic magazine. In 2009 he received the Griffin Museum of Photography’s Susan Sontag Scribe Award for best photographic writing. Hart has written several books on photographic subjects, including the Prentice-Hall college textbook Photography, the original Photography For Dummies, and As I Found It: My Mother’s House, his newly published photographic monograph from German art book publisher Kehrer Verlag.

Online: russellhartphoto.com

View the Exhibition in full 360˚

Exhibition: Thursday, July 17th – September 12th

Opening Reception: July 17th 5:00 – 8:00pm

Book Signing & Artist Talk: July 18th, 4:00 – 6:00pm

Gallery Night Reception: August 15th 5:00 – 8:00pm

On View: Thursday, April 17th – September 12th

The RI Center for Photographic Arts, RICPA 118 N. Main St. Providence, RI 02903

Located in the heart of Providence, RICPA was founded to inspire creative development and provide opportunities to engage with the community through exhibitions, education, publication, and mutual support.

RICPA exists to create a diverse and supportive community for individuals interested in learning or working in the Photographic Arts. We strive to provide an environment conducive to the free exchange of ideas in an open and cooperative space. Members should share a passion for creating, appreciating, or learning about all forms of photo-based media. We work to provide a platform for artistic expression, that fosters dialogue and drives innovation in the photographic arts.

We are member supported, the first step to membership is registration – https://www.riphotocenter.org/registration Details on membership options can be found at https://www.riphotocenter.org/membership-info

The Gallery at the Rhode Island Center for Photographic Arts is a member of Gallery Night Providence https://www.gallerynight.org

Questions: Contact gallery@riphotocenter.org To learn about other RICPA exhibits and programs, visit https://www.riphotocenter.org

Leave a Reply